Why Did I Conduct This Research?

As the eldest brother, I felt it was necessary to understand the streets for myself. I still remember the moment I realized that people do not speak classical Arabic in the streets, and that Spacetoon was merely an unreal, fictional world.

It became easy for me to see how disconnected I was from the outside world, with many unspoken and spoken languages that I wouldn’t understand as a “home kid” at six years old.

Can you imagine me returning home with shoe prints on my clothes, hiding them so that my mother wouldn’t know I was bullied at school? Since I was supposed to protect my younger siblings, my journey to understand the streets began in a rather complicated way, starting from fights, small gangs, hiding places, bikes, and finally the meanings of clothing.

In Jeddah, we would notice well what others were wearing, yet at the same time, we wouldn’t treat them based on that. This allowed me, as Ahmad, to live in Al-Sharafiya for a long time before my Quran memorization teacher told me: “Ahmad, these colors don’t suit the street.” He spoke like an older brother who understood my cultural and social background.

“Your mother is a teacher, right?”

“Yes.”

“And she chooses your clothes?”

“Yes.”

“I understand you well; you need to pay attention to the colors that young men wear in the street.”

The essence of his words for me was simple: I should wear sportswear or a thobe, and if I ever wore any color, it should be earthy tones or jeans. This conversation faded from my mind, but the advice remained: “Wear what you like, but also wear what pleases others.”

From there, I started to interfere more in my mother’s aesthetic decisions. As you know, this wasn’t easy.

Since I was young, I subconsciously developed a theatrical personality using whatever was available at home to design clothes resembling those of characters from movies, series, and dreams. I also remember when I got to university and found versions of my old self who didn’t know the colors of the street, and I began to tell young men whose stories seemed similar to mine that “these colors aren’t worn in the street.”

But who decided what colors and clothing were appropriate for the street?

The Questioning Stage

What should we wear in the street, and what should we not wear? Who decides what is acceptable and what isn’t? I remember the first man I saw with henna in the street. I recall seeing men wearing flowers during our trip to the south. I remember the principal at school who had kohl on his eyes, and when I asked, they said it was a tradition.

I recall how the young men of Jeddah started styling their hair in “kdash,” which was previously known as “qaza,” and later the trend of headbands and buckles coincided with BlackBerry devices. This always left me wondering when, how, and why we do these things. Who determines public taste? How did the world come to know the thobe and undershirt? And how did they disappear again? What is the Saudi being trying to express?

Intermix Residency

My acceptance into the Intermix residency allowed me the opportunity to study and ask all the questions that have occupied my mind. Do we dress to be beautiful, or are we not concerned at all? What does beauty even mean? This was the fundamental question that motivated me.

I happened to have an interest in aesthetics and had books on the subject, so I read four books on aesthetics that gave me a deeper understanding of society and how we perceive beauty collectively.

Here are the key takeaways related to the topic:

- Subtle Beauty vs. Striking Beauty: Eastern societies tend to prefer harmonious and understated appearances over loud and flashy ones, especially in social occasions. “Don’t show off,” my father would say every time I bought new shoes and wanted to flaunt them. This social trait contrasts with another that is more about individualism.

- Showiness: For various social reasons, we generally dislike showiness and have an inherent sense that glaring beauty is often accompanied by some form of negativity (like being a “wanna-be” or showing off).

- Is Beauty an End in Itself or a Means?: It was hard to recall any situation or action we undertake collectively or individually purely for the sake of beauty. There’s always a reason linked to others, society, status, religion, etc.

Before forming a conclusion, I decided to be fair and ask people to gather accurate information. Thus, I conducted a study that included:

- Surveys to reveal the identity of respondents.

- Discussion groups.

- Individual interviews.

- Interviews with various segments of society.

The Survey

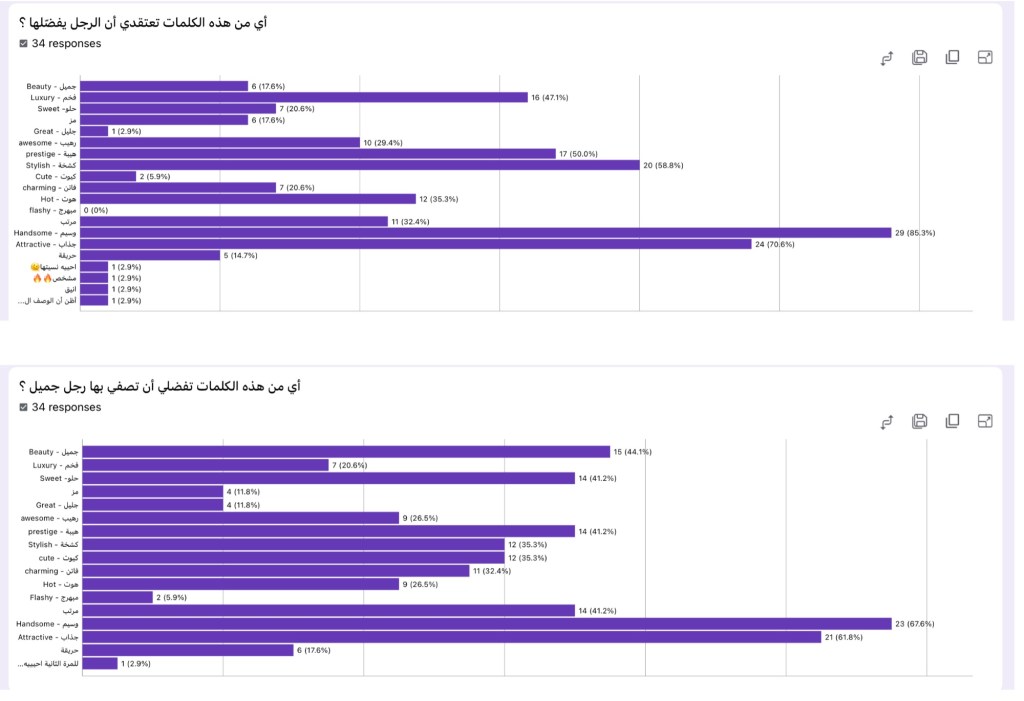

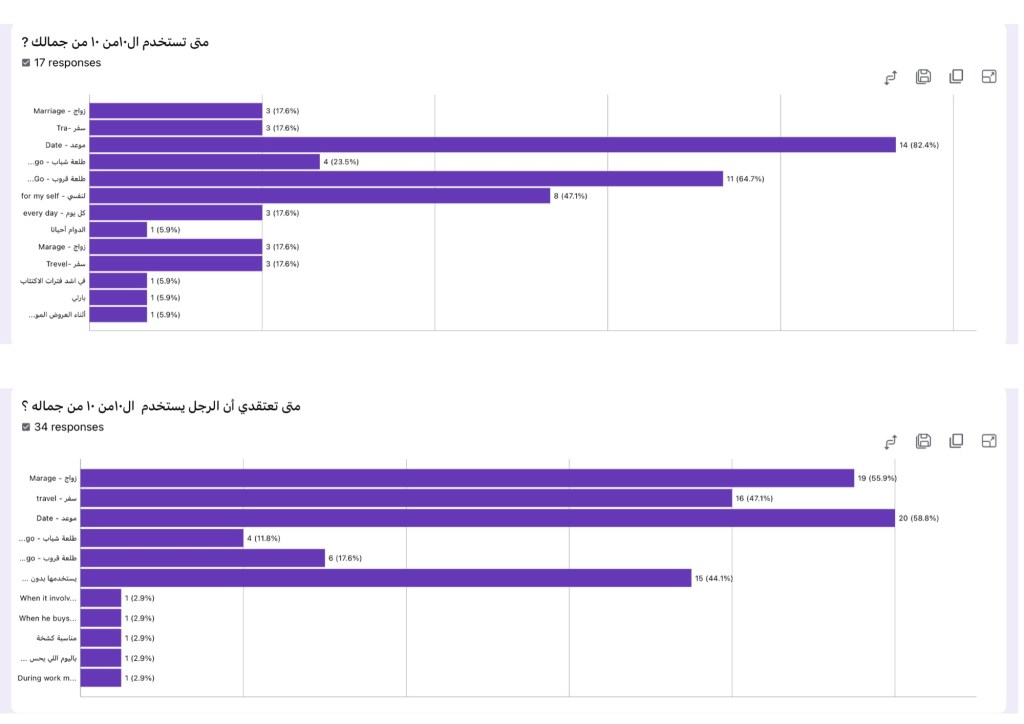

I created two types of surveys: one directed at men and another at women. The questions differed between the two, and I aimed to understand their economic and social situations and their views on beauty. The reactions to the questions varied widely and were sometimes shocking.

Here’s the translation of your text into English:

And some of the open-ended questions were:

If your appearance were to say a sentence or a word, what would it be?

For example: “I am organized and cool, hiding a deep life,” or “I am a conservative family man who values authenticity and traditions,” etc. Feel free to describe.

Describe how your clothing and accessories convey this message.

For example: “I believe that my choice of shoes gives me a cool appearance; my shemagh is always white, which gives a sense of positivity and happiness,” etc.

- Eccentric with a colorful vibe

- Responsible, neat, charismatic

- “I am a person who wears whatever makes me feel good about myself, regardless of what others think.”

- “Usually, I try to wear pieces that set me apart from my peers. I try to wear clothes that show my identity. I wear a green scarf that expresses holiness.”

- “I like to look like a boss 😎🔥.”

- “My choice of black in my clothing (which is predominant) gives a mix of elegance, authority, and mystery.”

- “I am an artist and a bit mysterious; I care about myself, but not excessively, just enough to show that I care.”

- “The silhouette and color harmony.”

- “I am bold in my appearance, and I always say, ‘Dress like you are partying, and party like a rock star.'”

- “I have multiple styles in my clothing: rock, bohemian, casual, and sometimes smart casual. My style draws attention; I seek harmony between colors and styles with elements reflecting parts of my personality. For example, I might wear bohemian clothing suggesting a calm person (for yoga and meditation), but I could also wear a ring or a skull necklace, reflecting the artist within me (like someone once told me, ‘You look like an artist’).”

- “Distinct and different with a confident personality.”

- “Secret.”

- “I can never be ordinary.”

- “Old school.”

- “Cool and neat.”

- “My choice of colors and accessories and my attention to my body make me very attractive.”

Do you remember when someone complimented your beauty? What exactly did they say?

“Confident, not caring how people think of you.”

“I don’t really focus on that.”

“Man, what do you eat? It’s not normal how handsome you are.”

“You are handsome.”

“Good-looking.”

“Your smile is nice.”

“I love the shape of your head; being bald suits you.”

“Can I take your picture?”

“Beautiful smile, dressing nicely, nice eyes, etc.”

“No.”

“That I have such pretty eyes.”

“Damn man… You look so great, bro—literally!” 🤣

“My smile is nice, and my beard is nice.”

The compliments were often about my style; no one has ever commented on my physical handsomeness.

“You are amazing—your personality is attractive.”

“Man, you look really clean.”

As for the individual interviews, discussions, and random street interviews, the summary was:

- “We talk” meme

The unconventional exposes you to public opinion, which can deprive you of a job, marriage, or harm your reputation and your family’s reputation, or label you with an undesirable stigma. - Unity of Thought

Uniqueness in appearance equals uniqueness in thought and beliefs. It indicates a life that is enticingly personal and often does not resemble public social life. Intellectual uniqueness is somewhat acceptable, but belief uniqueness is not. - Colors and Deviance

Colors and attention to appearance are more associated with femininity than masculinity. Thus, they are linked to men with non-normative inclinations, which raises questions about that individual. - Individuality (Showiness)

We often try as young men to stand out in the details that matter to us, such as the fabric of the thobe, the type of eastern attire, etc. - Comfort

In general, any comfortable clothing is welcomed and considered beautiful, even if it belongs to other cultures. In the research, I conducted interviews with young men from the Asir region in Khamis Mushait and found that 3 out of 5 young men had Pakistani, Sudanese, or Egyptian clothing, with the common trait being: “Man, it feels like you aren’t wearing anything.” - Layers and Modesty

Clothing that describes the body is not favored in any way and may pass if it is a trend, but it is impossible for it to last. - Body Shaming

- The Trend Comes from a Quirk

In all the interviews I conducted, the young men talked about their experiences in designing things very different from society and confronting society with them. Sometimes it was an attempt to create a trend, sometimes it was an attempt to express oneself, and sometimes it was without any clear reason. The common thread among them was:

“I know people will mock me, but it’s okay; I want to be different, and maybe after a while, someone will imitate me.”

The conversations were beautiful and enriching, and it’s hard to summarize them here, but the essence is:

There are no specific colors or defined patterns for designs and recognized boundaries, but there are certain determinants. The difference between a limit and a determinant is that a limit restrains your progress, while a determinant is internal and prevents you from stepping out.

So:

- Belonging, Harmony with Surroundings

Harmony varies in context: tribal, social, within the framework of friendship, family occasions, etc.

All forms of belonging are characterized by certain traits:

- Loose Clothing: Eastern men tend to wear clothes that do not clearly describe the body, and there are many reasons for this.

- Layers: Despite the hot weather in the Kingdom, men in Saudi Arabia consider wearing more than one layer a symbol of beauty.

- Display of Abundance: Symbols of abundance vary from generation to generation, but they appear in cleanliness, shiny accessories, brands, and anything that shows a person as a business owner or in a high position, etc.

- Cleanliness: Grooming, creams, perfumes, shoes, and light colors are seen as signs of beauty and care for Eastern men.

- Accessories: Men are more inclined to express their personal traits through accessories rather than clothing—bracelets, rings, prayer beads, watches, canes, glasses, etc.

- Non-Formal Traits: Men believe their beauty and attractiveness show through their achievements, character, history, lineage, position, possessions, and how these reflect on their appearance and movements more than anything else.

- Head Covering: Eastern men tend to cover their heads with various items that could adorn the head, such as glasses, shemaghs, agals, turbans, crowns, and they greatly wish to wear earrings, but society prohibits this. A mustache is also considered a sign of beauty, along with a thick beard.

In a way, I found that the more a man covers his identity with things, the more attractive he becomes. In a conversation with a group from the Asir region, I found that comfort is a very high value, even if it is drawn from another culture.

Personal Conclusion:

Manhood is not something acquired; it is a given that cannot be taken away from you, especially in clothing. The more at peace you are with yourself and listen to the voice in your head, the more this will reflect in your outward appearance because the inside is simply a reflection of the outside.

Dressing Based on Personality:

Often, our old photos are funny when we were children because they represent our mother’s or father’s taste from a past era. In reality, they are clothes chosen based on your personality in their eyes. The first time we find that these clothes do not resemble our peers’ clothing, we start demanding clothes that resemble everyone else’s so that we do not appear different and can fit in well.

From here, the name of the work came, which is the official response to our interference in their taste (“Well, I grew up and became…”).

Individuality:

In all the interviews, there was a recurring phrase: “Wear something that resembles you and represents your personality.” Despite the simplicity of this phrase, there is a long story behind it: you cannot wear something that resembles you if you do not know who you are in the first place. If you do not have an internal journey to discover yourself, your issues, your true personality, and so on, you will only be able to decide who you are at that moment, and only then can you wear something that truly resembles you.

The Result:

An artwork titled “I Grew Up.”

Materials:

Transparent fabric (organza) to showcase the layers and nuances that we go through.

Each layer represents a phase that the Saudi man goes through:

- The First Layer: Childhood, the completely free and creative part, very personal and innocent, represented by a colorful flower.

- The Second Layer: The body, our different bodies, which are often not ideal, and which we often try to cover with other layers. In this layer, there is a cap (just a headscarf).

- The Third Layer: Nonexistent; this layer represents the role of parents in trying to give the individual a unique identity. It is nonexistent because I needed a longer study on fabric and lighting to show the details well.

- The Fourth and Final Layer: Represents belonging and similarity—thobe, shemagh, pen, and collar.

There are seven characters in the studio, all looking at a massive thobe in the center of the studio. Inside the thobe, there is a living flower trying to emerge but unable to.

The work is accompanied by soft piano music alongside a popular song.

Artistic Statement:

You Grew Up

2024

Fabrics, Acrylic Colors, Performance Art, Installation

2.30 m * 3 m * 2 m

“Every pepper to become a man”

“These colors aren’t worn by men”

… and other phrases I heard in my childhood and obeyed, trying to maintain masculinity as a status, not just an assigned trait.

My artistic personality observed my mother as she went to school as an English teacher, wearing vibrant colors every day, which brought joy and happiness to people. She often wondered about these standards: Who set them? Are they written somewhere? A brief catalog or code that I could memorize and embody? I couldn’t find this agreed-upon code, so I tried to create one based on the voice of society at large, which I thought contradicted my mother’s views.

I chose beauty/appearance because it’s the most tangible aspect we interact with daily, yet we rarely talk about it, despite its significant impact on the details of our lives. After detailed research, I decided to represent society through seven different characters, each with three completely different layers, except on the surface.

I chose organza fabric for its transparency.

- The first layer represents the childish, innocent, and completely free side, which often tries to break out of the ordinary.

- The second layer represents the body in all its forms, both its ugliness and beauty.

- The final layer represents the social garment that covers everything mentioned before, reflecting the beauty of belonging and equality.

All the different characters look at a massive thobe that contains a living flower trying to emerge from it but unable to do so. The living flower symbolizes a human performer wearing bright colors, representing individual attempts to break out of the ordinary and expand social boundaries. It signifies that the energy inside is still you and that the beauty within is your truth trying to tell you something.